The DNA of Community Revitalization and Human Resource Development (2)

- The Soul of a "Kawasuji-mon" Who Turned Deserts Green -

Feature PICK UP 若松ゆかりの著名人

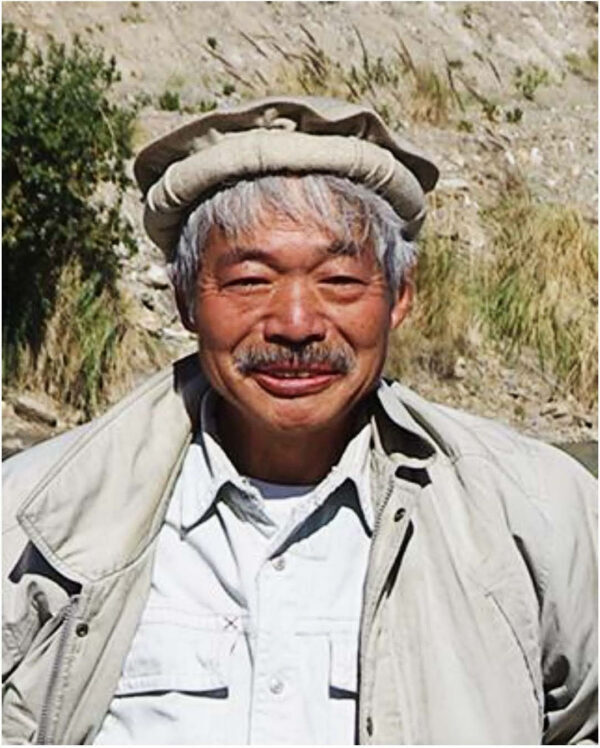

Dr. Tetsu Nakamura

Near Jalalabad in eastern Afghanistan, Dr. Tetsu Nakamura brought water to what was once a vast wasteland, reviving the greenery. His journey was far more than just the charitable work of a single physician. It was driven by a passion for "community building" nurtured by the landscape of his hometown, Wakamatsu, a DNA of "human development" inherited through his lineage, and a "profound reverence for life" held since his youth. Just as a single drop of water nourishes the parched earth, the legacy he left behind continues to light the flame of hope in people's hearts across borders.

The Lineage of the Tamai Family and the "Insect Boy"

To trace the roots of Tetsu Nakamura, born in Fukuoka City in September 1946, one arrives at a rough yet warm-hearted culture in Wakamatsu known as the "Kawasuji spirit." His maternal grandfather, Kingoro Tamai, led the "Tamai-gumi" stevedore group and was a man of strong ethics who would "help those in need regardless of profit or loss."

His character inherited the humanity of his father, Tsutomu. After marrying Hideko, the daughter of Kingoro, Tsutomu ran a small stevedoring company called "Nakamura-gumi." While immersing himself in the harsh harbor sites where rough men gathered, he was also an intellectual involved in labor movements, even engaging in literary debates with Hideko's brother, Ashihei Hino (Katsunori Tamai). Dr. Tetsu Nakamura’s persona—operating heavy machinery while covered in mud, yet calmly critiquing civilization and engaging in writing—vividly evokes the honest and steadfast life of his father, who was a committed social activist

However, among these boisterous figures, young Tetsu was a shy and quiet child. He preferred to leave the noisy world of adults behind and venture into the fields and mountains of Wakamatsu alone. He chased tiny lives like butterflies and longhorn beetles. Aspiring to be an entomologist after being inspired by Fabre’s "Souvenirs Entomologiques," he spent his days observing insects.

His uncle, Ashihei Hino, was a significant influence; Nakamura frequently visited Hino’s residence, "Kahakudo," and together they walked the mountains and seas of Wakamatsu. Through their shared devotion to insect collecting, Nakamura unconsciously absorbed a deep respect for nature and the cycles of life.

The Impact in Pakistan

His love for insects never cooled. As a university student trekking through the mountains of Kyushu, he developed a longing to see the Parnassius (alpine butterflies) that inhabit high-altitude regions between 3,000 and 5,000 meters.

After graduating from Kyushu University’s Faculty of Medicine and becoming a psychiatrist, Nakamura joined a 1978 expedition to the Hindu Kush mountains as a team doctor to reach the foothills where these rare butterflies flew. During this trip, he was deeply shocked by the tragic conditions of leprosy patients in Pakistan, which ignited in him a powerful sense of mission.

Driven by the belief that "the work no one else wants to do is the work I should do," he decided to serve in Pakistan in 1984 as a member of the Peshawar-kai. It was a decision that manifested the "Kawasuji spirit" in his blood—a display of manly courage and devotion.

While treating leprosy patients and providing medical care to Afghan refugees fleeing war, Dr. Nakamura began working inside Afghanistan in 1986, opening clinics in mountainous areas to expand medical support.

Then, in 2000, a catastrophic drought, said to be the worst in history, struck. Drinking water vanished, and livestock were wiped out. Millions of people abandoned their villages in search of water. Infectious diseases spread among children who drank what little muddy water remained. The situation was desperate.

Land moistened by waterways drawn using traditional Japanese techniques.

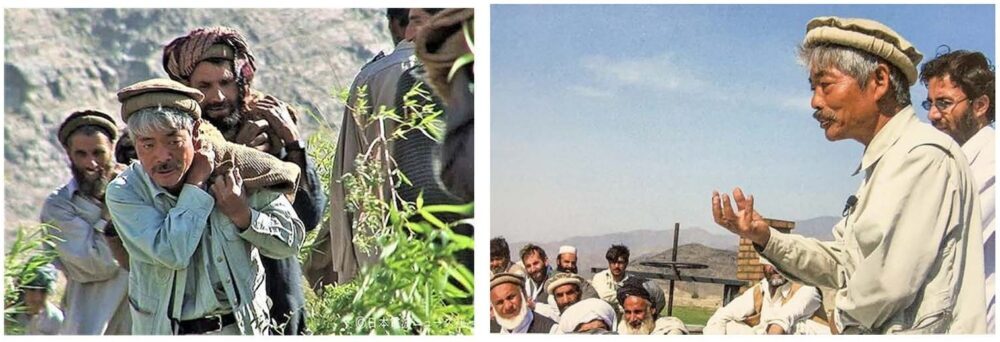

On the earth cracked by drought, children were dying not for lack of medicine, but for lack of water. "Medicine cannot cure hunger. With water, they can live on their own," Nakamura became convinced. In 2003, under the slogan "One irrigation canal rather than 100 clinics," he began the construction of the Marwarid Canal. He learned to operate heavy machinery himself and worked alongside the locals to excavate the land.

However, the construction of the irrigation canals was far from a simple civil engineering project; it was a continuous battle against the fury of nature, where the ravages of war were compounded by alternating cycles of drought and flood. The construction site was in a region of extreme heat, with summer temperatures soaring above 50°C, and was repeatedly struck by massive floods after work began. At times, the revetments and weirs they had painstakingly built were swallowed by muddy torrents, reducing months of labor to nothing. Often, massive bedrock would block the excavation route, presenting obstacles that manual labor and outdated heavy machinery simply could not overcome.

Furthermore, they faced the risks of workers being kidnapped and the construction site becoming a battlefield. To dispel the mistrust of the locals, Nakamura worked in the mud beside them, gradually building a relationship of trust.

As a result of these hardships, the 25km canal was completed in 2010. It transformed the former wasteland into 16,000 hectares of green land, supporting the lives of 650,000 people. This project, embodying the phrase "Sho-Isshu" (To light up a corner of the world), tells the story of how an approach that stays close to nature and people is more important than mere technical perfection.

Furthermore, in the absence of specialists, Dr. Nakamura looked to the "Yamada Weir" flood control techniques developed by the Fukuoka Domain during the Edo period. These sustainable methods utilized locally available stones and bamboo, ensuring that even if the structures were damaged, the local farmers could repair them themselves. Rather than relying on concrete, these stone-masonry weirs worked in harmony with the river's natural flow. This approach was also a practical application of the "coexistence with nature" that he had learned from Fabre in his youth.

Though he fell to an assassin's bullet, the water continues to flow.

In December 2019, while traveling in Jalalabad, Dr. Nakamura was attacked by an armed group and passed away at the age of 73. The news plunged the people of Afghanistan into despair and Japan into deep mourning.

The Afghan government granted him honorary citizenship, and local farmers call him "Kaka Murad" (Respected Uncle/Elder), continuing to protect the canals he left behind.

What Dr. Nakamura practiced in Afghanistan was not merely "aid." It was the act of sowing the seeds of "human development" nurtured in Wakamatsu in a distant land. Just as in the phrase he loved to write, Sho-Isshu (Light up your corner), he shone his light as brightly as possible in the place he was given. The DNA he left behind is now being carried forward into the next phase of "community development" by the hands of Afghan farmers and the Japanese youth who follow in his footsteps.

"For the Good of the World and Mankind" Anime Series: The Story of Tetsu Nakamura -The Doctor Who Turned Parched Land Green

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=mHNSZskiRMU

Tetsu Nakamura Project: Sustainable Support for Afghanistan for Generations to Come<>br https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=kjk3lgS7_1g