Giants of Community Revitalization (4)

Wakamatsu as Portrayed by Ashihei Hino and a Life of Passion

Feature PICK UP 若松ゆかりの著名人

火野葦平

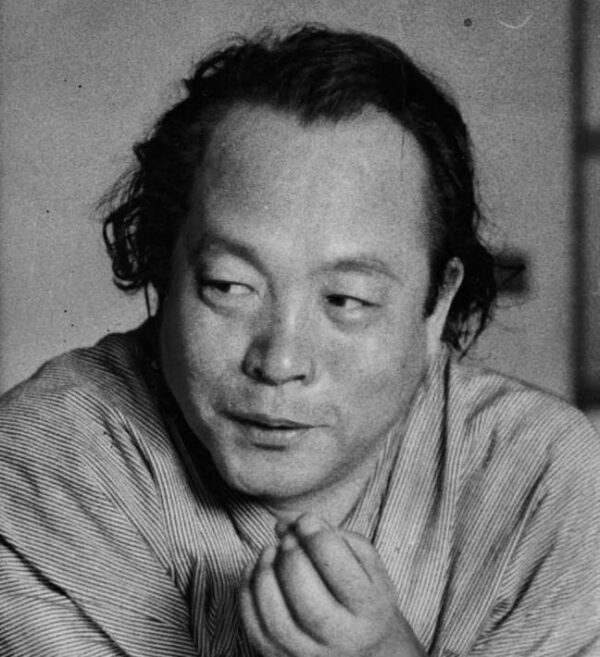

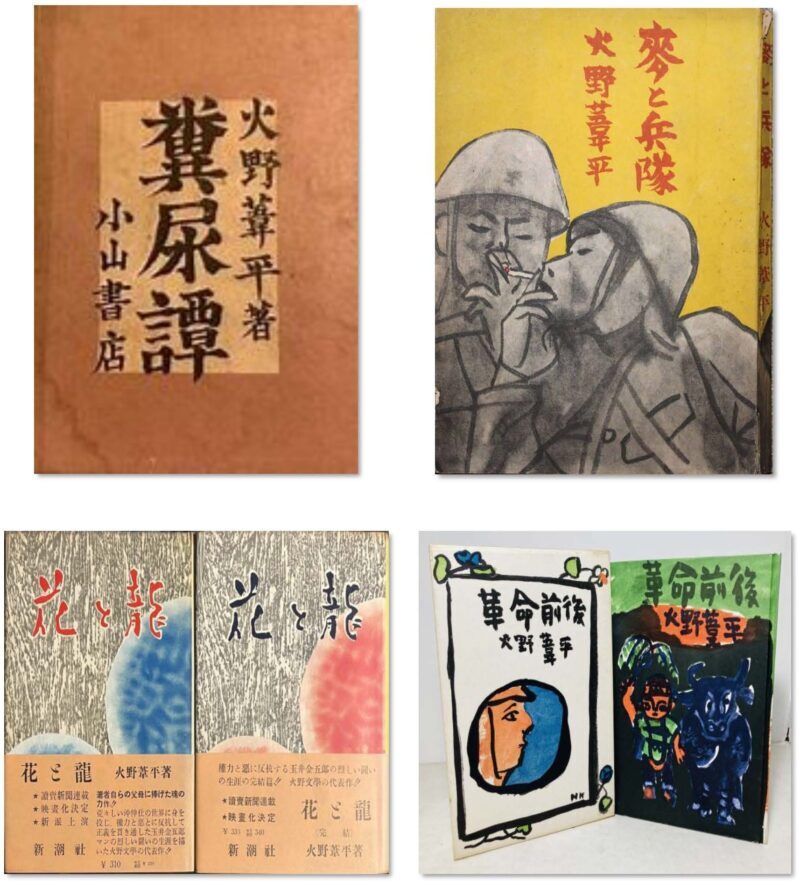

In 1938, at the age of 31, Ashihei Hino won the 6th Akutagawa Prize for FUNNYOTAN (The Tale of Excrement and Urine). He later became a bestselling author with war chronicles such as Wheat and Soldiers. After the war, he once again reached the pinnacle of literary success with FLOWER AND DRAGON a novel depicting the world of dock laborer the roots of his own life. This work vividly conveyed to the nation the energetic streets of his hometown Wakamatsu, its sense of duty and compassion, and its overwhelming vitality, elevating the soul of the town into literature. Behind his bold literary career, however, Hino faced harsh postwar criticism and deep creative anguish, ultimately meeting a dramatic end by taking his own life.

The Choice of a Young Literary Aspirant

Ashihei Hino (real name: Katsunori Tamai) was the eldest son of Kingorō Tamai, who hailed from Matsuyama in Shikoku. Leaving his hometown, Kingorō worked as a dock laborer under harsh conditions in Shimonoseki and Moji before moving to Wakamatsu with his wife Man. There, he founded the port cargo-handling business known as the “Tamai-gumi.”

Born in January 1907, Ashihei graduated from the former Kokura Middle School (now Kokura High School) and went on to study English literature at Waseda University. His studies were interrupted by military service, and after his discharge he chose not to return to university but instead went back to Wakamatsu to support the family business.

Behind this decision lay a complex mix of factors: his father Kingorō’s way of life, a sense of responsibility toward the family business, and his own ideological struggles. At the time, as mechanization advanced at Wakamatsu Port, small operators dependent on manual dock laborers faced severe difficulties, and the Tamai-gumi was no exception.

For Ashihei, conscious of his role as the eldest son who must support his father and provide for the family, the sight of laborers working desperately amid mud and coal dust revealed a profound “truth.” Dropping out of university meant turning away from “the intellectual world of Waseda” and stepping onto “the same ground as the laborers alongside his father.” More than his father’s wishes, it was Ashihei’s own inner transformation that led him to decide to remain in Wakamatsu.

Wartime Achievements and Postwar Literary Activities

In November 1937, Ashihei Hino published FUNNYOTAN in a literary coterie magazine, using the night-soil collection trade as its subject. He continued writing the work until receiving his draft notice for service in the Sino-Japanese War. After completing the manuscript, he entrusted it to a friend and departed for the front.

In February of the following year, FUNNYOTAN won the 6th Akutagawa Prize. One of the judges, Haruo Satō, praised it highly, stating that although it dealt with a vulgar subject, its overwhelming vitality and affirmation of human dignity possessed a strength and freshness unseen in existing literature.

News of the award was conveyed through military channels to Hino’s unit stationed in Hangzhou on the Chinese front. The fact that an ordinary private had won a major literary prize at the battlefield was unprecedented and attracted nationwide attention.

Subsequently, WHEAT AND SOLDIERS (1938), based on his experiences as a soldier, became an extraordinary bestseller in wartime Japan, firmly establishing Hino’s status as a national writer. This work, together with the so-called “Soldier Trilogy,” realistically portrayed the daily hardships of enlisted men while also enhancing his reputation as a “soldier-writer” supportive of national policy.

However, with the end of the war, Hino was subjected to harsh criticism as a collaborator and was purged from public office. After enduring this period of hardship, he reexamined his own literature and began serializing FLOWER AND DRAGON in 1953, a long novel modeled on his family’s history. The work once again became a social phenomenon and a major hit. It was a significant postwar achievement that bridged serious and popular literature, demonstrating his revival and rich literary sensibility.

His Role in Revitalizing His Hometown, Wakamatsu

Through his many works, Ashihei Hino spread the image of his hometown Wakamatsu throughout Japan, laying the groundwork for its development as a cultural and tourism resource. FLOWER AND DRAGON in particular, repeatedly adapted into films, left a strong impression of Wakamatsu as a bustling coal-shipping port, the chivalrous spirit of the “gonzō” dockworkers, and the town’s deep human warmth and fiery temperament.

Fond of local kappa folklore, Hino also produced many works featuring kappas, such as STONE AND NAIL and KAPPA MANDALA, adding earthy humor and fantasy to the charm of Wakamatsu.

His imaginative fusion of postwar hopes for peace with the legend of the “Kappa-Sealing Jizō” at Mount Takato gave rise to events combining torch processions and kappa festivals. The annual “Fire Festival,” held in late July, has become a summer tradition in which many citizens carry torches as they make their way to the summit of Mount Takato.

Furthermore, Hino wrote the lyrics for GOHEITA-BAYASHI a local performing art, reinterpreting as “local pride” the tradition of Goheita-boat pilots who once carried coal across Dokai Bay and beat rhythms on the sides of their boats. It has since become an indispensable form of entertainment at the annual Ashihei Memorial Ceremony held in late January and at local festivals.

A Literary Resolution Completed Through Death

On January 24, 1960, Ashihei Hino took his own life in his study at home, known as Kahakudō. He was 53 years old.

Although his death was initially announced as due to heart failure, his family revealed in March 1972—twelve years later—that it had been suicide by sleeping pills. Various factors have been cited, including his anguish as a “war-responsible writer” and anxiety over physical decline. In his suicide note, he reportedly wrote:

“I am going to die—not like Ryūnosuke Akutagawa, perhaps, but because of a certain vague anxiety. I am sorry. Please forgive me. Farewell.”

His final work, BEFORE AND AFTER THE REVLUTION was serialized in the magazine Chūō Kōron starting in May 1959 and published in book form on January 30, 1960—six days after his death. This long novel, in which Hino, once famed as a “soldier-writer,” depicted the turmoil before and after Japan’s defeat, his own war responsibility, and the shifting postwar climate, was highly acclaimed and received the 16th Japan Art Academy Prize.

Kahakudō https://www.japanheritage-kannmon.jp/concierge/shop_detail.cfm?id=84

Ashihei Hino Memorial Museum : https://www.japanheritage-kannmon.jp/concierge/shop_detail.cfm?id=111

Chikuzen Wakamatsu Fire Festival :