Giants of Regional Revitalization (3)

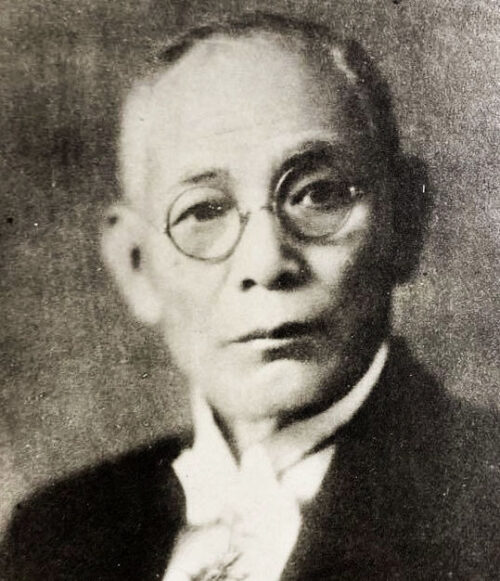

Isokichi Yoshida: An Unconventional Politician Who Spanned the Meiji, Taishō, and Shōwa Eras

Feature PICK UP 若松ゆかりの著名人 若松百年史

吉田磯吉

A funeral attended by more than twenty thousand people. Wakamatsu Station overflowing with mourners, and a farewell ceremony attended even by a former prime minister. In January 1936, one man was laid to rest. Isokichi Yoshida—who appears in Ashihei Hino’s novel Flowers and Dragons—was known as the “Great Oyabun of Kyushu,” an extraordinary figure who never harmed others throughout his life and who later distinguished himself as a member of the National Diet. Rising from poverty to the pinnacle of the kawasuji-mon (river men), and eventually ascending to the stage of national politics, his life was truly a mirror reflecting both the light and shadow of modern Japan.

From “Kawahirata” Boatman to Great Oyabun

Born in June 1867 in Ashiya Village, Onga District (present-day Ashiya Town), Isokichi Yoshida’s life was far from smooth. His family had long been retainers of the Matsuyama Domain, but when his father, Tokuhei, deserted the domain, the family wandered from place to place before settling in Ashiya. When Isokichi was still young, his father died, leaving the family in dire poverty. They eked out a living by digging for shellfish at sea and selling them at roadside stalls, and at times were scorned by the local community as outsiders.

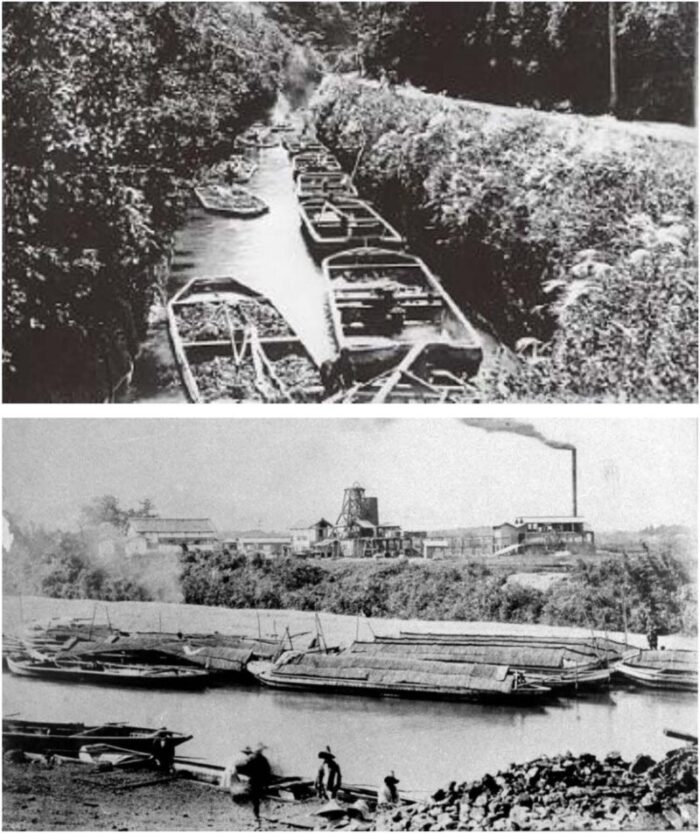

At the age of sixteen, Isokichi became a boatman on a kawahirata, plying the Onga River. With his exceptional physical strength and courage, he soon distinguished himself, and through his associations with the kawasuji-mon, he gradually stepped onto the path of the chivalrous underworld.

By the end of the nineteenth century, however, the times were changing dramatically. With the opening of the Chikuhō Industrial Railway, river transport on the Onga River went into steady decline. Quick to read the signs of the times, Isokichi shifted his base of operations to the emerging port city of Wakamatsu. While lodging with his married sister, he rose to prominence among the chivalrous factions there.

In 1901, construction began on the government-run Yahata Steel Works across the water in Yahata. Drawn by the economic boom, companies and shops of all sizes poured in from across the country. Laborers and drifters from all over western Japan flocked to Wakamatsu, and amid the growing disorder of this burgeoning city, Isokichi began to establish a unique position for himself.

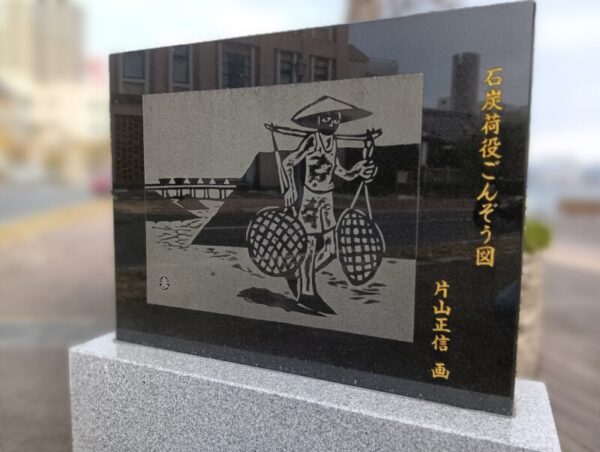

At the time, Wakamatsu had become one of Japan’s largest coal-shipping ports. Through the harsh labor of coal loading and unloading, a distinctive “river-men temperament” and culture emerged. During the peak years from the Meiji through Taishō periods, nearly four thousand coal stevedores—known as gonzō—were said to have worked there, supporting the city’s vitality.

Active as a Chivalrous Politician

The Meiji era, which accelerated Japan’s modernization, naturally accepted the oyabun–kobun (boss–follower) relationship and sought mediators imbued with a chivalrous spirit.

In this context, Isokichi—who combined physical strength and courage with keen intelligence as a mediator and adviser—made his name in 1910 by settling a fierce dispute that erupted when Hanaregoma, an ōzeki of the Osaka Sumo Association, transferred to the Tokyo Sumo Association.

Later, at the age of forty-eight, he was elected to the House of Representatives for the first time and joined the Minseitō Party. In 1921, he gained nationwide fame by preventing in advance an attempted takeover of Nippon Yūsen by the Seiyūkai Party.

At the time, the political world openly operated on the logic of “controlling violence with violence,” and politicians were expected to possess such prowess. Even in this rough and turbulent political arena, Isokichi earned widespread respect for his exceptional ability to mediate disputes and for his personal charisma. He remained active in national politics for seventeen years, until 1932.

His friendship with Shigemaru Sugiyama—who spent his childhood with Isokichi in Ashiya Village and later came to be known as the “power broker behind the scenes” of politics—is said to have supported Isokichi’s political activities.

Contributing to the Community Through Enterprise

Isokichi Yoshida also demonstrated remarkable talent in the business world, contributing not only to his hometown of Wakamatsu but to the broader industrial development of northern Kyushu. He helped bring order to the turmoil accompanying the establishment of the government-run Yahata Steel Works, and based himself at Wakamatsu Port, a key hub for coal distribution, where he undertook numerous business ventures.

He served as president of companies such as Hirayama Coal Mine, Yoshida Trading, Wakamatsu Fish Market, and Wakamatsu Transport, developing businesses across a wide range of fields including mining, logistics, and commerce. He is also said to have been involved in the founding of Sankyū Transport, Otani Coal Mine, and the Tobata Fish Market.

He further distinguished himself in dispute mediation and industry coordination. In 1916, a conflict arose between the Wakamatsu Coal Merchants’ Association and the Fishermen’s Association over the recovery of coal that had sunk in Dokai Bay. Through Isokichi’s mediation, the dispute was amicably resolved. As an adviser to the Coal Mining Mutual Aid Association, he also contributed to strengthening cooperation within the mining sector and to expanding the economy and employment of the Wakamatsu region.

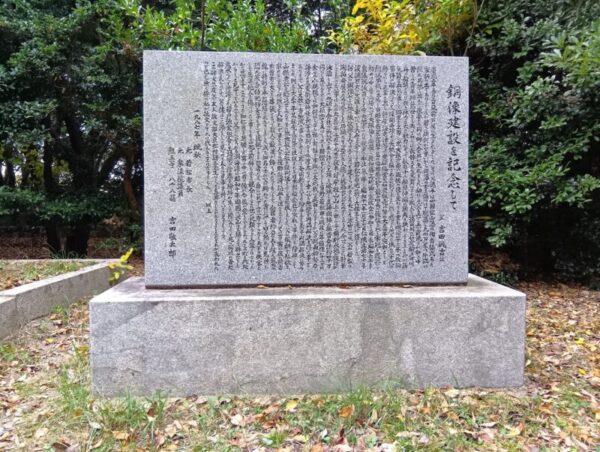

The bronze statue that stands in Takato-yama Park bears witness to his role as a local leader who tirelessly mediated disputes and troubles and was beloved by many citizens. It would not be an exaggeration to say that Isokichi Yoshida’s activities had a profound influence on the formation of the region’s identity.

The Father as Seen by His Son, Keiichirō

On January 17, 1936, Isokichi passed away at the age of seventy. Despite snowfall on the day of the funeral, more than twenty thousand people attended—exceeding the number of households in Wakamatsu City at the time (approximately thirteen thousand). The long funeral procession included a former prime minister, the president of the Minseitō Party, city and prefectural assembly members, reservists, firefighters, youth groups, members of the Patriotic Women’s Association, and even geisha. The entire city turned out to bid him farewell.

Yoshida Keitarō (Isokichi’s adopted son), who later became a Protestant minister, is said to have watched this grand funeral with mixed emotions.

An inscription accompanying the statue on Mount Takato reads:

“…With not even a single tattoo upon his body, a chivalrous man of the realm who never harmed another throughout his life, an oyabun without a single criminal record—truly without equal in this world…”

Seeking neither reward nor personal gain, he devoted himself quietly and selflessly to aiding and rescuing countless people, constantly mediating conflicts and troubles and bringing about reconciliation. Such a benevolent character, together with his deep love for his hometown of Wakamatsu, may well represent the true figure of Isokichi Yoshida.