Giants of Regional Revitalization (2)

The Life and Legacy of Keitaro Sato

Feature PICK UP

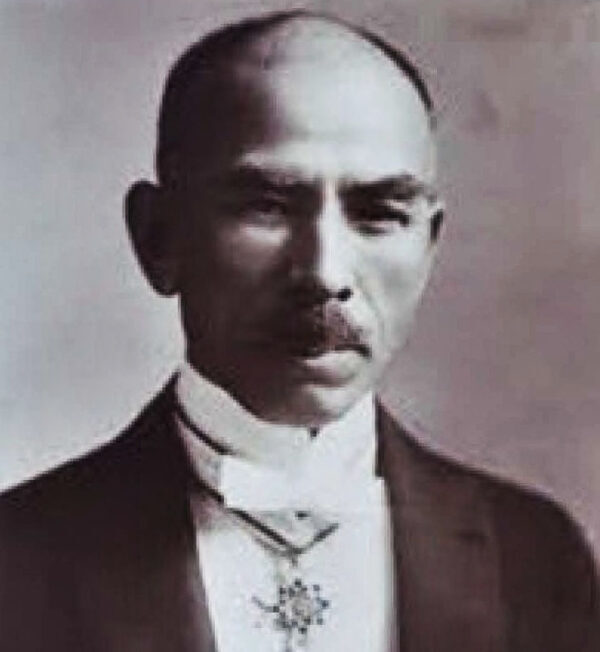

佐藤慶太朗

Keitaro Sato—known as the “God of Coal”—was an extraordinary figure who amassed a vast fortune as an industrialist and devoted almost all of it to the public good. His life was defined by an unyielding pursuit of success and by grand philanthropic undertakings rooted in his conviction that “public and private are one.”

Deeply inspired by Andrew Carnegie, the American steel magnate who pledged to return all the wealth he had earned to society, Sato sought to embody the same principle. His contributions—including support for the founding of the Tokyo Prefectural Art Museum (today’s Tokyo Metropolitan Art Museum)—remain a profound legacy that continues to shape Japan’s modern cultural, educational, and social foundations.

Frustrated Dreams and New Challenges: His Struggles in Youth (1868–1892)

Keitaro Sato was born in 1868 in Jinnoharu Village, Onga District (now Yahatanishi Ward, Kitakyushu City), as the eldest son of Sato Kosaku. He grew up amid the sweeping transformations of the Meiji era, a period marked by dramatic shifts from the old order to a new national structure.

Aspiring from a young age to become a lawyer, Sato enrolled in 1886 at Shuyukan, officially known as the Fukuoka Prefectural English School, an institution that inherited the traditions of an old domain academy. However, determined to pursue a legal career, he left Shuyukan to move to Tokyo with financial support from relatives. In 1887, he entered Meiji Law School (the predecessor of Meiji University). At the time, Meiji Law School was renowned for its high-quality instruction grounded in French legal studies, producing many distinguished jurists.

Driven by the dream of becoming a lawyer, Sato pushed himself to study relentlessly. But his naturally frail health deteriorated, and he developed severe beriberi—then a widespread national illness—forcing him into a prolonged period of recuperation. Unable to continue on the legal path, he returned home in deep disappointment, compelled to abandon his aspirations.

The Birth of the “God of Coal”: Success as an Industrialist (1892–1922)

After spending some time in recuperation, Keitaro Sato resolved to rebuild his life. In 1892, he headed to Wakamatsu, which was rapidly developing as a major hub for coal transport in Kyushu. There, he found employment at Yamamoto Shutaro Shoten, the leading coal trading firm in Wakamatsu. He later married Toshiko, the younger sister of Shutaro’s wife, and learned the fundamentals of commerce—including bookkeeping—directly from her.

Sato quickly distinguished himself. With his sharp insight and tireless work ethic, he mastered every aspect of the coal trade. He studied coal quality so intensively that he was said to be able to identify the exact Chikuho mine from which a piece of coal had been extracted simply by handling it. Eight years after joining the company, in 1900, he left Yamamoto Shokai to establish his own enterprise, Sato Shoten.

The success of Keitaro Sato as a businessman can be attributed above all to his extraordinary foresight in recognizing the future potential of Wakamatsu Port and to the innovative distribution methods he developed.

During the late Meiji and Taishō periods, Wakamatsu Port grew rapidly as a major coal-exporting port, providing the essential energy source that powered Japan’s modernization. Sato not only worked within existing distribution networks but also devised a groundbreaking new system: loading coal directly onto steamships anchored at Moji Port, rather than relying on the traditional multistage, labor-intensive transshipment process. This innovation greatly improved both speed and cost-efficiency in logistics, solidifying Wakamatsu’s competitive advantage in the coal trade.

He further expanded coal demand by marketing Ōkuma coal—often shunned for its lower quality—to industries such as ceramics and whaling. This raised both the reputation and overall circulation of Chikuho coal and contributed significantly to enhancing Wakamatsu’s standing as a major coal-exporting port.

Recognizing the surge in coal demand following the Russo-Japanese War, Sato ventured into coal mine management in 1908. From coal brokerage to mine operation, and ultimately into trade, shipping, and warehousing, he expanded his business empire. His remarkable abilities and achievements in the coal industry earned him the title of the “God of Coal.”

In 1918, he was elected to the Wakamatsu City Council and later became its chairman. In 1920, he also assumed the role of auditor for Mitsubishi Mining. However, following the advice of his physician, who worried about the worsening of his chronic health condition, Sato gradually withdrew from front-line management around this time.

Wealth as a Trust from Society: Sato’s Philosophy of Philanthropy Rooted in “Public and Private as One”

A defining feature of Keitaro Sato’s life was his unwavering belief in “public and private as one”—a conviction that the great fortune he had amassed should be returned to society.

He was deeply moved by the famous words of American steel magnate Andrew Carnegie: “The man who dies rich dies disgraced.” Sato adopted a philosophy that viewed wealth as something entrusted to him by society, and returning it to society as his natural responsibility. His philanthropy was not mere charity; it was an ambitious effort aimed at cultivating culture and building the foundations of society.

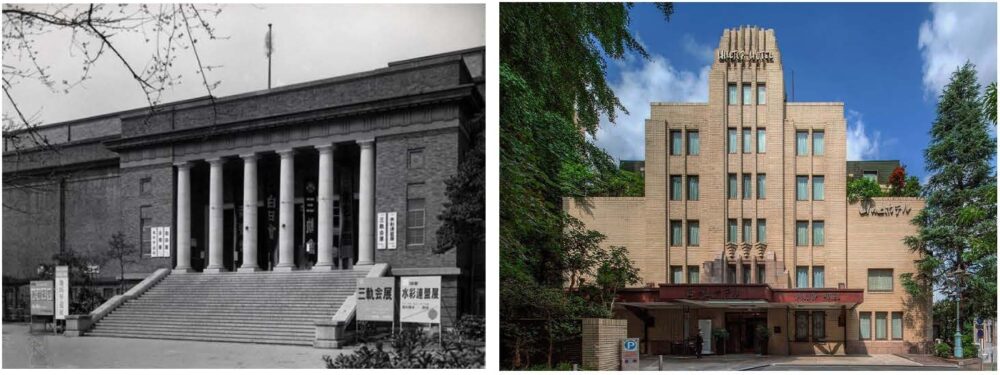

Among Sato’s many philanthropic achievements, his support for constructing the Tokyo Prefectural Art Museum (now the Tokyo Metropolitan Art Museum) stands out as especially symbolic. In 1921, he learned that Japan’s first public art museum—whose construction had already begun—was on the verge of cancellation due to a lack of funds. Believing firmly that “only through the establishment of a permanent art museum can we protect classical works and foster new art,” he considered a public art museum indispensable for Japan’s cultural development.

Responding immediately to the crisis, he pledged a full donation of 1 million yen (equivalent to approximately 3 billion yen today)—an unprecedented sum at the time. Thanks to Sato’s decisive action and extraordinary generosity, the Tokyo Prefectural Art Museum opened successfully in 1926.

This became one of Japan’s pioneering examples of modern philanthropy. Today, a bronze bust of Keitaro Sato sculpted by Fumio Asakura stands in the museum’s Art Lounge, preserving his legacy for future generations.

Sato also worked to improve the foundations of everyday life. In 1935, he established the Greater Japan Life Association to support poverty relief and education. In 1937, he built the Sato Shinko Seikatsukan—which cost 1.5 million yen (about 4.5 billion yen today)—as the movement’s headquarters. The building (now the main wing of the Hilltop Hotel in Surugadai, Tokyo) was an advanced social welfare initiative aimed at addressing poverty.

Having once aspired to become a lawyer himself, Sato strongly believed in the importance of expanding legal education for women. He made a major donation toward the construction of the school building for the Women’s Division (Law and Commerce) of Meiji University, founded in 1929. His support helped establish one of Japan’s earliest educational institutions that publicly recognized women’s right to study law.

His Later Years and a Legacy Passed Down Through Generations

Even after withdrawing from front-line business management, Sato’s passion for contributing to society remained undiminished. In 1934, he donated his vast estate and residence at the foot of Mount Takato to the City of Wakamatsu. The site is now Sato Park, a beloved place of relaxation for local residents. After the donation, Sato moved to Beppu for recuperation and passed away there on January 17, 1940, at the age of 71.

Sato ensured that his philosophy of “public and private as one” would endure after his death. Through his will, he donated all of his remaining assets—188 million yen (equivalent to roughly 5.6 billion yen today). The funds were used to build the Beppu City Art Museum and gymnasium, as well as to establish the Sato Scholarship Foundation dedicated to supporting young people.

Throughout his life, Sato embodied the ideal combination of modern entrepreneurial spirit and philanthropy. The fortune he built through Wakamatsu’s coal industry—and the reputation that earned him the title “God of Coal”—was converted into cultural institutions in Tokyo, educational and welfare foundations in Kitakyushu, and cultural facilities in Beppu. These contributions continue to form part of Japan’s cultural and social infrastructure across generations.

His steadfast belief that “wealth is something entrusted by society” remains an important guiding principle for contemporary business leaders and asset holders when considering their responsibilities to the community.

Keitaro Sato and the History of the Tokyo Metropolitan Art Museum https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=WyHVd-SwsMQ