The Lasting Legacy of “Wakamatsu Spirit”

Genealogy of Tamai Kingoro and Man, Hino Ashihei and Nakamura Tetsu

Feature PICK UP

Dr. Nakamura Tetsu (boy wearing a cap marked N), Hino Ashihei behind him, and Ms. Tamai Man standing at the left

Photo courtesy of Hino Ashihei Museum

Why “Hana to Ryu” (Flowers and Dragons) Now?

Before the film version of the novel Hana to Ryu (Flowers and Dragons) started production in Kitakyushu, the actor Mr. Iwaki Koichi made a courtesy visit to Fukuoka’s prefectural office.

This article on the internet caught my attention and made me wonder.

“Why Hana to Ryu in this modern age?”

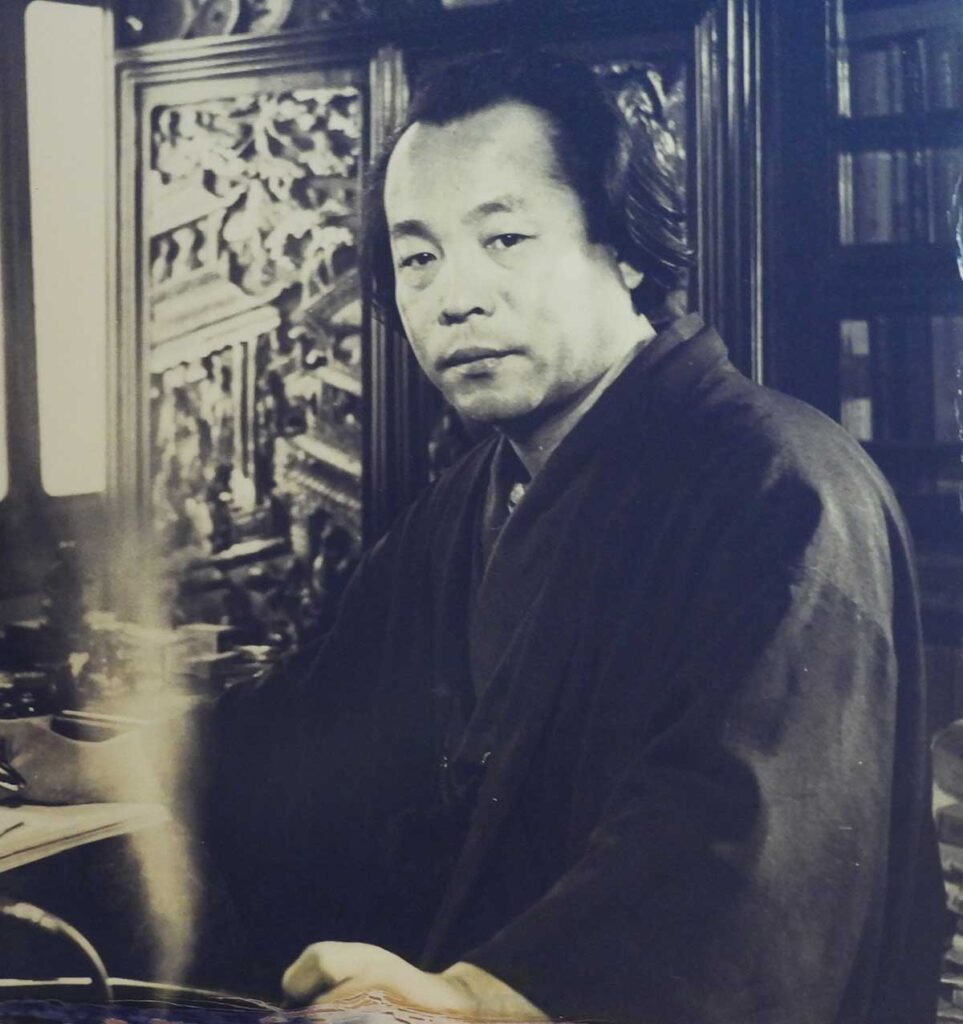

Although it is an excellent novel that has been cinematized six times so far, today there may be many who do not know the author Hino Ashihei or the story itself.

I gave a brief explanation to them. Hana to Ryu is a novel that Hino Ashihei from Wakamatsu in Kitakyushu wrote, which was based on his parents.

Photo courtesy of Hino Ashihei Museum

It is an eventful family history of Tamai Kingoro and his wife Man in Kitakyushu that runs from the mid-Meiji era to immediately before the Sino-Japanese War. My explanation did not seem to have meant much to my younger acquaintances. Although I was talking as if I knew the novel well, I had actually read it quite a long time before, so I took this opportunity to reread it.

Reading again, I was surprised at how interesting the story was. It was hard to believe that it was written 70 years ago. I also realized that I previously misunderstood the character of the protagonist, Tamai Kingoro.

Probably because of the impression made by Mr. Takakura Ken playing Kingoro in a film, I thought Kingoro was a violent man whose fists responded before his mouth. In the novel, however, he was depicted as a man of righteous mind who hated violence and gave the highest priority to the betterment of laborers’ lives.

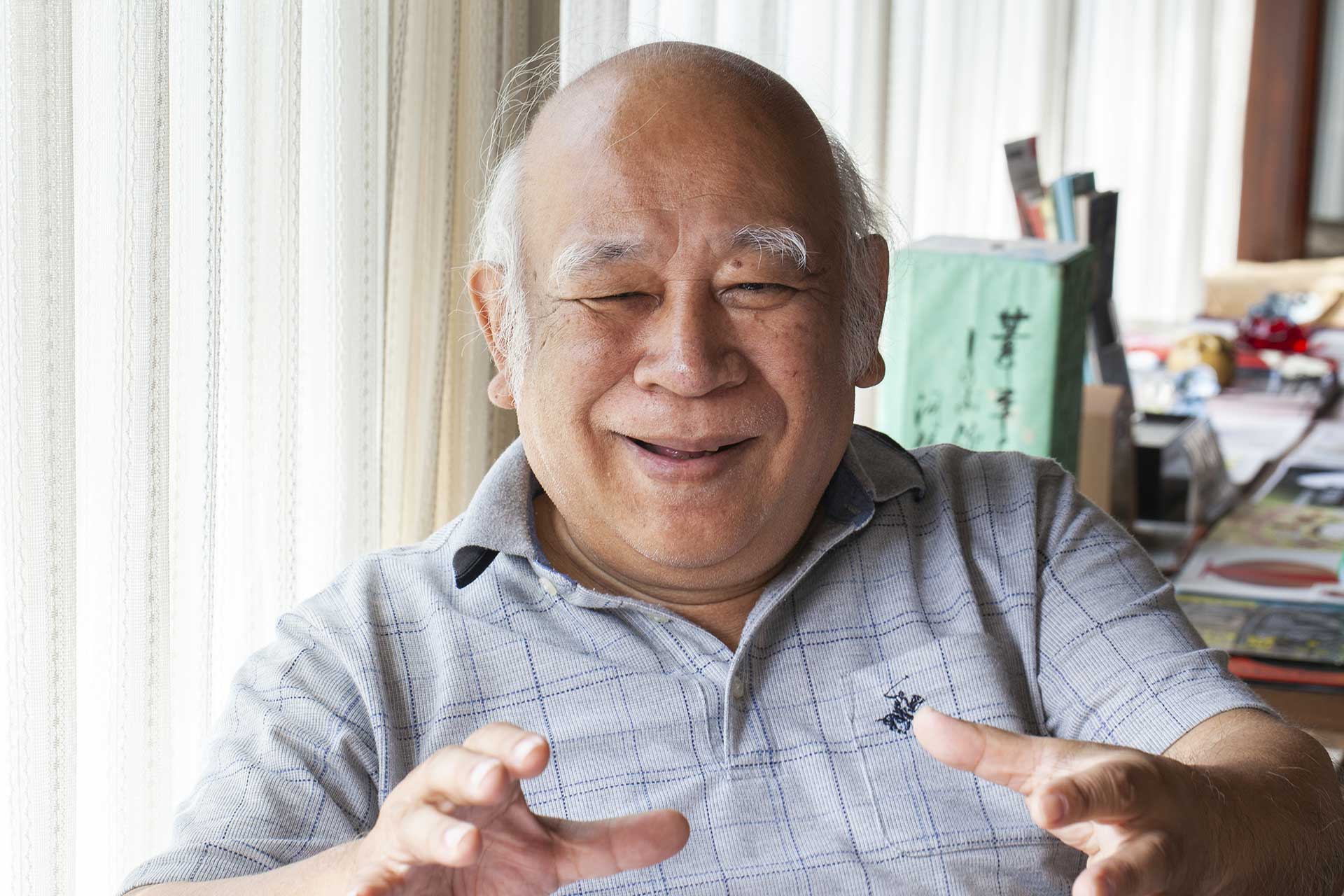

Wanting to know a little more about Kingoro after finishing the novel, I Googled a newspaper article that revealed that Dr. Nakamura Tetsu had a photo of his grandfather, Tamai Kingoro, displayed in his room in Afghanistan.

Dr. Nakamura built irrigation canals in war-torn Afghanistan to save the lives and livelihoods of 650,000 people. His mother, Hideko, was the second daughter of Tamai Kingoro and Man. Their eldest son, Hino Ashihei (real name: Tamai Katsunori) was Dr. Nakamura’s uncle.

Tamai Kingoro and Man worked hard for laborers without giving in to the powers of the time, Hino Ashihei devoted his life to literature and depicted the joy and sorrow of ordinary people, and Dr. Nakamura Tetsu staked his life for 30 years on the reconstruction of Afghanistan, although he was shot to death before completing this life ambition.

What was common among these three people? What was the influence of Wakamatsu, the city that produced them? What was their long-held spirit?

To solve these many questions that grew in my mind, I visited Mr. Sakaguchi Hiroshi at “Kahakudo” in Wakamatsu. Mr. Sakaguchi is the president of the Hino Ashihei Shiryo no Kai.

Hino Ashihei lived in “Kahakudo” for most of the period between 1940 and his death in 1960, where he created many works including Hana to Ryu. Kahakudo means the dwelling of kappa (a mythical creature in Japan) and, because Hino Ashihei passionately loved kappa, his residence was so named.

Mr. Sakaguchi had a close friendship with Dr. Nakamura, as well, and he is currently engaged in the management and operation of Kahakudo and the Hino Ashihei Museum.

What Is Kawasuji Katagi?

“What do the three have in common besides their blood relationship?”

After a hurried greeting, I rushed into this question as I was eager to find the answer. With a soft smile, Mr. Sakaguchi replied.

“It would be kawasuji katagi. In a word, it is the spirit of siding with the weak and crushing the strong. I believe that temperament has been kept continuously from Tamai Kingoro and Man, to Hino Ashihei, and to Nakamura Tetsu.”

Kawasuji Katagi is the temperament found in many people living and working in the Onga River basin, an area called Chikuho, which supported the coal industry with Wakamatsu as the coal shipping port. Rough tempers but warm hearts. Having the full freedom of mind to treat strangers without any prejudice.

“Wakamatsu was formed by strangers from other parts of the country who were attracted by the wealth offered by coal. That is why the spirit to help each other grew. I have long been insisting that kawasuji should become a universal term used worldwide. By writing it in Roman letters ‘KAWASUJI,’ I believe it can be the only moral or concept of values that can counter neoliberalism and the law of the jungle. Wakamatsu was an international place because it was a port town where people came from diverse foreign countries. Therefore, I think Wakamatsu has concentrated the ‘KAWASUJI’ spirit, and that is why I want to transmit ‘KAWASUJI’ from Wakamatsu to the world.”

Looking at Mr. Sakaguchi laughing light-heartedly, I imagined people around the world chanting ‘KAWASUJI,’ which made my heart jump. Wanting to hear more, I asked him about the personalities of each of the three.

The first was Tamai Kingoro. According to the novel Hana to Ryu, Kingoro was born in Ehime, and Taniguchi Man was born in Hiroshima. Both left their hometowns with ambition and arrived in Moji. Kingoro and Man met when they were both working on the docks and got married in 1903.

1903 was when the Wright brothers succeeded in launching the world’s first powered flight and when the first street cars began operating in Tokyo. Moji and Wakamatsu were boisterous towns with booming economies because of the local coal mines.

At that time Man was 20 and Kingoro was 24 years old.

Kingoro had a sense of exaltation facing Dokai Bay, with its heavy ship traffic, surrounded by the chimneys of the three towns of Tobata, Wakamatsu and Yahata.

Photo courtesy of Hino Ashihei Museum

Compelling Points of Each of the Three

To my question of what was especially compelling about Tamai Kingoro’s character, Mr. Sakaguchi said,

“He was a typical man with kawasuji. He never gave an inch, even to a giant corporation such as Mitsui or Mitsubishi, regarding things that were not reasonable in light of the spirit of mutual support. Yet, his wife, Man was a remarkably brave woman, braver than her husband. Brave as he was, Kingoro would have been no match for Man. (laugh)”

It was Man who ruled the family after Kingoro’s passing. She would often sit near the brazier with perfect composure, smoking tobacco with a long pipe.

Regarding his grandmother, Dr. Nakamura wrote in his book of what he heard her say at times, such as “take the lead in standing up to protect the weak” and “respect life no matter how tiny it is,” and how these ideas were deeply ingrained as his ethics.

As to Hino Ashihei,

“He had many distinguished achievements as a writer. In less than one year after receiving the Akutagawa Prize, he began writing serialized novels simultaneously on two major newspapers, The Asahi Shimbun and Mainichi Shimbun. During the war, he went to the front as a reporter in the information corps of the Japanese army. He wrote Mugi to Heitai (Wheat and Soldiers) and other works there and became a bestselling author overnight. That’s quite something.”

At 31, he received the 6th Akutagawa Prize for “Funnyotan” (Tales of Excrement and Urine), which is a novel filled with humor and pathos literally related to excrement and urine. It was in 1938 when the National General Mobilization Law went into effect.

One of the selection committee members, Kikuchi Kan, commented, “Awarding the prize to an unknown budding writer agreed with the founding purpose of the Akutagawa Prize and gave us a great deal of satisfaction. Although the title is filthy, the work itself is brilliant, including the orderly and neat descriptions, with a vigorous style, yet rather detailed in expression, and having a slight pathos.”

This unknown writer went to the battlefields and described the stories he saw and heard there in “Mugi to Heitai” (Wheat and Soldiers) and other novels, and quickly became an author of bestsellers.

Mr. Sakaguchi said, “He was a shy guy. I think he was not much of a sake lover, but he probably drank reluctantly out of need as it was rather difficult for him to meet and talk with people when sober. He was ardent in cultural activities in the community, hoping to deliver culture and literature that were as high quality as possible. It is not common that a national-level author strives so hard for the sake of their local community.”

Dr. Nakamura Tetsu spent his early childhood in Wakamatsu and saw his uncle, Hino Ashihei many times. Looking at the poem inscribed on Ashihei’s literary monument, “The scent of a single chrysanthemum, inserted in a knapsack smeared with dirt. The blue of the sky was bright and clear to the eyes of the soldier traveling on a road in a foreign land,” he wrote as follows:

“The poem inscribed on the literary monument at the top of Mt. Takato overlooking Wakamatsu Port touches my heart. That poem explicitly expresses the beauty of humanity he loved so immensely, and a human spirit that tries to find a sparkle of beauty even in the weakness or ugliness of humans.” (From “Ten, Tomoni Ari” (Providence Was with Us))

I asked Mr. Sakaguchi what Dr. Nakamura was usually like. “He also was a very shy person. He was no good at speaking and seemingly brusque. He would answer a question if asked but never became talkative voluntarily. He just worked hard in silence. His nature strongly resembled Kingoro and Ashihei.

Nobel Peace Prize to Peshawar-kai

Dr. Nakamura was born in Fukuoka City in 1946, the year Emperor Hirohito issued the Humanity Declaration. After graduating from Kyushu University, he became a physician. He first worked in hospitals in Japan and then took a position at Peshawar Mission Hospital in Peshawar, Pakistan, where he was engaged in the treatment of leprosy and other diseases. He later expanded his medical care activities to refugee camps and mountain regions. However, when severe drought hit Afghanistan, Dr. Nakamura, laying his life on the line, dug wells and built canals, which he taught himself to do because to supply medical care alone was not enough to save lives. His projects irrigated 16,500 hectares of land, which is twice the area of Wakamatsu Ward, and saved the lives of 650,000 people.

“I think Dr. Nakamura showed us the ultimate kawasuji temperament. Sadly, his life was cut short, but if you want to know what kawasuji is, look at how he lived and what he did. That should be the quickest way to learn it. I hope that the Nobel Peace Prize will be given to Peshawar-kai, which he founded and which has been continuing its activities and his mission even today. I think the activities of Peshawar-kai are of that magnitude as a social movement.”

Lastly, I asked Mr. Sakaguchi about the spirit of Wakamatsu that produced Tamai Kingoro, Hino Ashihei and Nakamura Tetsu.

Photo courtesy of Peshawar-kai/PMS

‘KAWASUJI’ Will Save the World.

“Ordinary people have supported the modernization of Japan, and the temperament of kawasuji was generated in that climate. As I said at the beginning, many think that today’s new capitalism will not be the solution to our society but have no idea what they should do. What I would like to propose at this point is the kawasuji temperament. Help the weak, crush the strong, and extend aid to those who are in need. If this moral is maintained, people can live happy lives. Rather than feeling intimidated or frightened in a society ruled by the law of the jungle, we should all have the spirit of kawasuji. So, I have been proposing a dream that we make ‘KAWASUJI’ a universal term, used worldwide, and save the world with a movement that starts in Wakamatsu (laugh).”

Looking at Mr. Sakaguchi laughing aloud with his eyes narrowed, I felt pleased knowing that here was another ‘KAWASUJI’ man. So, I shook hands with him, saying I would like to share your dream. I left Kahakudo with a bounce in my step.